Sonja Sekula was born on April 8, 1918, in Lucerne, Switzerland. Her mother Berta Huguenin was part of a well-known café and confectionery dynasty in Lucerne, while her father Béla Sekula worked as a stamp dealer. As her father travelled regularly, Sekula had the opportunity to visit places such as Italy, Hungary, and Paris, where she explored museums and connected with relatives. She attended prestigious boarding schools in Lucerne, Zuov, and Ftan from the age of seven. By 1934, Sekula was studying art history and painting in Hungary and Florence. When she was 17 she met and fell deeply in love with Annemarie Schwarzenbach, a highly respected Swiss photojournalist, and spent several weeks at her home in Engadin in 1936. This relationship ended abruptly when her father moved the family and his business from Lucerne to New York later that same year.

In 1938, Sekula's family moved to 400 Park Avenue and she enrolled at Sarah Lawrence College. After a trip to Europe that summer, Sekula made her first suicide attempt. Following this incident, her family placed her in psychiatric treatment at New York Hospital in White Plains, where she remained until 1941. When released Sekula studied at the Art Students’ League in New York. She took classes with Ukrainian-born painter Morris Kantor and Russian-born artist Raphael Soyer and formed a friendship with Robert Motherwell. Encouraged by her former teacher, Horace Gregory, Sekula also started writing. She studied the works of Gertrude Stein but despite her admiration, took the view that one must not “stick to the classics; stick to yourself.”

By 1942, Sekula had joined André Breton and his circle of Surrealists living in American exile. Among those she spent time with were Breton and his wife, Jacqueline Lamba, Roberto Matta, Suzanne Césaire, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Kurt Seligmann, Isabelle Waldberg, Yves Tanguy, Denis de Rougemont, and David Hare. In 1943, her work was featured in 31 Women, an exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, Art of This Century. Sekula also participated in the gallery’s Spring Salon for Young Artists alongside Pollock, Motherwell, and William Baziotes. That March, her writing was published for the first time in the journal VVV. Sekula spent the summer in Hampton Bays with Hare, Lamba, Breton, and his new protégé, the 17-year-old aspiring poet Charles Duits.

In 1945, Sekula fell in love with the painter Alice Rahon, who was married to the artist Wolfgang Paalen. They shared an affair that lasted several months and remained lifelong friends. Sekula stayed at Breton’s apartment at 45 West 56th Street that summer. In a letter to Rahon, she wrote: “But this summer has brought me real liberty—a true expression of peace and solitude.” Sekula travelled to Mexico to study Pre-Columbian art. Through Rahon, she met several artists, including Frida Kahlo, Gordon Onslow Ford, Leonora Carrington, and Remedios Varo. Upon returning to New York, the Sekulas hosted a farewell party for Breton before he departed Haiti, with guests including Anaïs Nin.

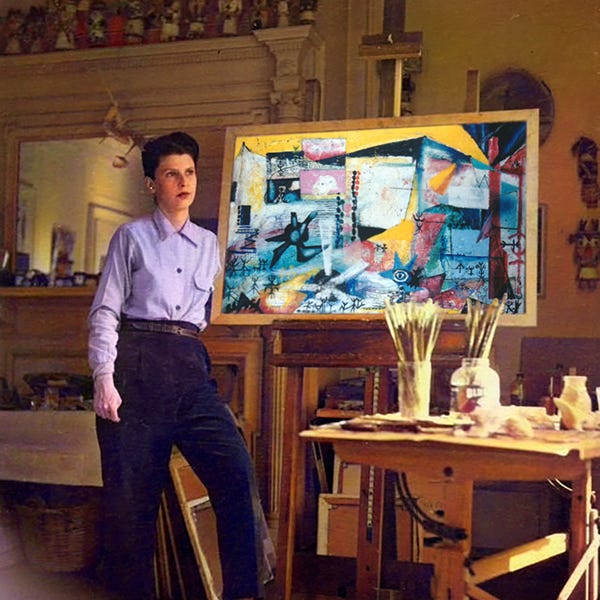

In May 1946, Sekula held her first solo exhibition at the Art of This Century gallery. She also visited Frida Kahlo, who was in New York for spinal fusion surgery. Sekula spent the summer at her family’s rented beach house in Asharoken, Long Island, with her partner, Natica Waterbury. The Hungarian-born photographer André de Dienes photographed her. She and Waterbury travelled to New Mexico in October and rented a house outside Sante Fe. Sekula was fascinated by Native American rituals, witnessing a nocturnal religious dance (Yébîchai) of the Navajo people and observing a sand-painting created for a healing ceremony, which was then destroyed at dusk.

In 1947, Sekula returned to New York and moved into a studio at 346 Monroe Street, home to John Cage and dancer Merce Cunningham. Although Cunningham typically preferred to design his own costumes, he commissioned her to create one for his performance of Dromenon. Through Cage, Sekula met painter Manina Thoeren, with whom she fell deeply in love. Sekula held the first of five solo exhibitions at the Betty Parsons Gallery the following year. The exhibition received critical acclaim, and she sold several works.

Years later, she recalls the inspiring atmosphere:

“With John Cage at Monroe Street in New York in my youth, I still felt a natural joy in life, there I could forget the surroundings I had been born into and become absorbed in the understanding of immediate communication. I miss the silent understanding of conversations and the cheerful company.”

In the spring of 1949, Sekula travelled to Europe, where she stayed for nearly two years, beginning in Paris. She spent the summer in St. Tropez with Thoeren. Sekula visited Capri with Waterbury in September and then went to Rome in October before returning to Paris. There, she lived in the same hotel as Waterbury and the writer Jane Bowles. Sekula met composer Pierre Boulez and visited Alice Toklas to view Gertrude Stein’s art collection. Through Breton, she met the poet, writer, and statesman Léopold Sédar Senghor. The following year, Sekula was included in a show at The London Gallery, managed by the surrealist dealer and artist E.L.T. Mesens. In November 1950, she set sail from Hamburg back to New York.

In April 1951, Sekula celebrated the opening of her third exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. She experienced a breakdown and returned to the psychiatric clinic at New York Hospital the following day. Her work was featured in the landmark exhibition, the 9th Street Show that May. Sekula was discharged from the hospital towards the end of the year and she moved back in with her parents. After attempting a career as a teacher, she returned to Switzerland with her mother in October 1952 where she was admitted to the Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen. Sekula was released the following autumn and stayed in Zurich with her mother. In 1954, she returned to New York before being admitted to the Hall Brooke Hospital in Connecticut.

Sekula contrasted her parents' and doctors' views on her illness with her own perspective:

"I have had enough experiences, including religious visions, that made my family believe I was 'sick.' Often, I was simply being true to my own rather mystically inclined nature.”

In 1955, unable to afford the high costs of medical treatment in the United States, the Sekula family returned permanently to Switzerland. That summer, they lived in the Chalet Opel in St. Moritz with engineer Fritz von Opel and his wife, Emita. Sekula developed an interest in Zen Buddhism, oriental painting and philosophy. Although she continued to travel with her family throughout the late 1950s, she sought psychiatric care several times.

At the end of January 1957, Sekula held her first solo exhibition in Switzerland at the Galerie Palette in Zurich. Afterwards she travelled to Paris with her mother and met Jean Dubuffet at an art opening. Sekula had her last exhibit at the Betty Parsons Gallery in May of that year. In 1958 she lived with her parents in Zurich, where she set up a studio in the basement. Sekula connected with Alan Watts, who lectured at the C.G. Jung Institute that spring. Encouraged by their meeting, she began rereading Watts' works and resumed her study of psychological and philosophical texts by Jung, Suzuki, Graf Dürkheim, and Eugen Herrigel. Sekula formed a friendship with the young Swiss artist Manon and maintained contact with photographers Roland Gretler and painter Oskar Dalvit.

By 1960, Sekula had formed a relationship with the teacher Sylvia Mosimann, and they briefly lived together at the Hotel Kaiser in Zurich. Sekula attended lectures by Dürckheim on Meister Eckhart and Zen, as well as those given by her friend, the psychologist Jolanda Jacobi. In 1961, she focused intently on her Meditation Boxes series. Sekula also frequented the Zurich Jazz Club, Africana, where she discovered pianist Champion Jack Dupree and met writer Max Bolliger, who published her work. She held various odd jobs while undergoing clinical treatment and continuing her art. On April 23, 1963, Sekula attended her mother's birthday with her family. However, after a female friend cancelled their visit to the Max Ernst exhibition at the Kunsthaus the following day, Sekula tragically took her own life on April 25. She is buried in St. Moritz, as she had requested in a final letter to her mother.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Angela Rose Design to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.