Artist and author Miné Okubo was born in Riverside, California, in June 1912. She was one of seven children of Tametsugu and Miyo Okubo, who moved to the United States in 1904 to represent Japan at the St. Louis Exposition of Arts and Crafts. Okubo’s father was a professor of Japanese history and philosophy, while her mother was a painter and calligrapher. Her mother frequently painted at home and encouraged her children to pursue artistic careers.

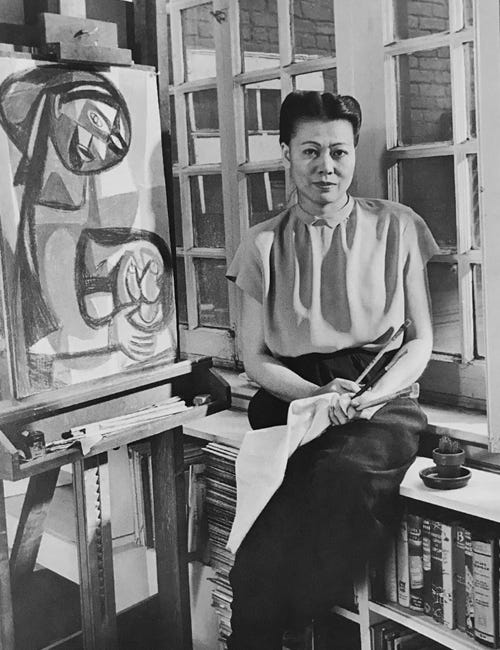

Okubo enrolled at Riverside City College at the age of 19. By 1933, she had received a scholarship to study art at the University of California, Berkeley, where she graduated in 1935 with a Bachelor of Arts. Okubo completed her master's degree the following year. She supported herself while studying by working as a seamstress, maid, farm labourer, and tutor. In 1938, Okubo was awarded the Bertha Taussig Travelling Art Fellowship which allowed her to spend 18 months in Europe. During her time in Paris she studied under the painter Fernand Léger.

In September 1939, Okubo found herself stranded in Switzerland due to World War II. She managed to obtain a visa and boarded one of the last ships leaving Bordeaux for the United States. Her return meant she could not complete the last six months of her fellowship. Once back in California, Okubo joined the New Deal’s Federal Art Project where she created mosaics and murals at Fort Ord on Monterey Bay and the Oakland Servicemen’s Hospitality House. She also collaborated with artist Diego Rivera at the Golden Gate Exhibition. During this period, Okubo curated two exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, showcasing the artwork she produced while studying in Europe.

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which resulted in the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans. Okubo's family received an official notice from the government in April, having three days to pack what they could carry, vacate their home, and report to a "central relocation station" in Berkeley. Her father was sent to a high-security camp in Montana as he was born in Japan. Four of Okubo's siblings were scattered among different camps while her older brother was mistakenly drafted into the military.

“We were suddenly uprooted—lost everything and treated like a prisoner with soldier guard, dumped behind barbed wire fence. We were in shock. You’d be in shock. You’d be bewildered. You’d be humiliated. You can’t believe this is happening to you. To think this could happen in the United States. We were citizens.”

Okubo and her brother Toku were assigned the family number 13660 and sent to the Tanforan detention camp in San Bruno, California. After six months of confinement, they were transferred to the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. These camps were prisons, having communal bathrooms, a lack of running water, no privacy, forced manual labour, curfews, and limited food. Despite the living conditions, Okubo continued to pursue art. She helped to establish the Tanforan Art School and later the Topaz Art School alongside Berkeley art professor Chiura Obata and other fellow artists. She also worked as an illustrator for the Topaz Times and contributed to the production of Trek, a literary magazine, designing covers and serving as its art editor.

Since only government-approved photographs were allowed, Okubo chose to document her confinement through drawings. She intended to act as both a camera and a record keeper, worried that the public would not believe what was happening. During her time in the camp, Okubo created over one thousand sketches of daily life. Her artwork included charcoal, watercolour, pen, and ink drawings, often focusing on the lives of women and children. The internees had daily work duties which meant that Okubo typically had to draw at night. She rarely slept for more than a few hours, as she was determined to capture the day’s events while they were still fresh in her mind.

In early 1943, Okubo submitted one of her drawings of a camp guard to an art show at the San Francisco Museum of Art, where it won a prize. Impressed by her talent, the San Francisco Chronicle commissioned her to create a series of sketches depicting life in the camp for their Sunday magazine. This caught the attention of the editors at Fortune magazine, who hired her to contribute to a special issue focused on Japan. With the support of Fortune, Okubo was able to leave Topaz in 1944 and move to New York. She settled into a studio apartment in Greenwich Village where she lived and worked for the rest of her life.

“As soon as all the passengers had been accounted for, we were on our way. I relived momentarily the sorrows and the joys of my whole evacuation experience, until the barracks faded away into the distance. There was only the desert now. My thoughts shifted from the past to the future.”

With encouragement from M. Margaret Anderson, the editor of Common Ground, a liberal pro-immigrant quarterly, Okubo organized an exhibition of her artwork in 1945. At the same time, she began compiling her drawings into a book titled Citizen 13660. Okubo arranged the sketches in a narrative sequence and drafted accompanying text recounting her experiences at the Tanforan and Topaz internment camps. Columbia University Press published the work in September 1946. Following the book's release, critics praised the unique and dramatic style of Okubo's ink drawings and concise writing describing the camp experience. It was the first memoir by a Japanese American incarcerated during World War II.

In 1948, designer Henry Dreyfuss commissioned Okubo to create a large Mediterranean map mural for the main foyer of a new fleet of ships, called "4 Aces," built for American Export Lines. She also continued working as a commercial artist and illustrator. Okubo's drawings appeared in numerous publications, including Time, Life, The New Yorker, and The New York Times. She illustrated books such as Where the Carp Banners Fly by Grace W. McGavran, Ten Against the Storm by Marianna Nugent Prichard, The Seven Stars by Toru Matsumoto, and Which Way Japan? by Floyd Shacklock. From 1951 to 1952, Okubo moved to California to work as an art lecturer at UC Berkeley before returning to New York City.

Okubo took on a new challenge in 1959 when the publisher Springer commissioned her to create illustrations for the anatomy textbook Clinical Coordination of Anatomy and Physiology. She later stated she had thoroughly studied and memorized anatomical details to create the drawings. In the 1960s Okubo returned to painting despite a decrease in her income. Her later works feature vibrant paintings of children, animals, and flowers, drawing inspiration from Japanese folk traditions. Okubo had an aversion to galleries and commercial sales, preferring to work primarily with individual patrons. By this time, her work had largely faded from public view, although CBS included an interview with her in the 1965 documentary Nisei: The Pride and the Shame.

During the 1970s, Okubo's work was rediscovered largely due to the Japanese-American redress movement. Her first major retrospective, Miné Okubo: An American Experience, opened at the Oakland Museum in 1972. In 1974, Okubo was honoured as the Alumnus of the Year by the Riverside Community College District. In the years that followed, she contributed to exhibitions showcasing artwork by former camp inmates and various Asian community newspapers.

In 1981, Okubo testified before the U.S. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, presenting a copy of Citizen 13660 as evidence. She also attended the U.S. Supreme Court hearings on the New Jersey class action lawsuit for internees, Hohri v. United States. A 1984 reprint edition of Citizen 13660 won an American Book Award. The Catherine Gallery in New York City hosted a retrospective exhibit the following year to celebrate 40 years of Okubo’s work. In 1987, the California Department of Education selected Okubo as one of twelve women pioneers in the state’s history. In recognition of her contributions, the Women’s Caucus for Art awarded her a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

Okubo continued to paint until the last months of her life. By the time of her passing in February 2001, she had built a personal collection of approximately 2,000 pieces of artwork which she stored in her studio and several warehouses. Following her wishes, Okubo's estate shipped nearly all of her archive to California, with the majority of the collection being sent to Riverside City College where she studied. The Okubo collection is permanently exhibited at the Center for Social Justice and Civil Liberties, which opened to the public on her 100th birthday in June 2012.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Angela Rose Design to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.